Recently, the Game Developers Conference (GDC) released its latest 2025 Game Industry Salary Report. The report, based on a survey conducted in July 2025, collected responses from 562 game industry professionals across the United States.According to the findings, the average annual salary for game industry professionals in the U.S. in 2025 is $142,000,middle of 129,000. Furthermore, 64% of respondents reported year-over-year salary increases.Notably, when compared to data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) for the same period (Q2 2025), which shows a national average salary of 67,000 anda median of 62,000, game industry salaries are significantly higher — it’s fair to say they “outearn the average by a mile.”

But High Salaries Don’t Buy Peace of Mind

Yet, despite the attractive paychecks, American game workers aren’t exactly at ease.

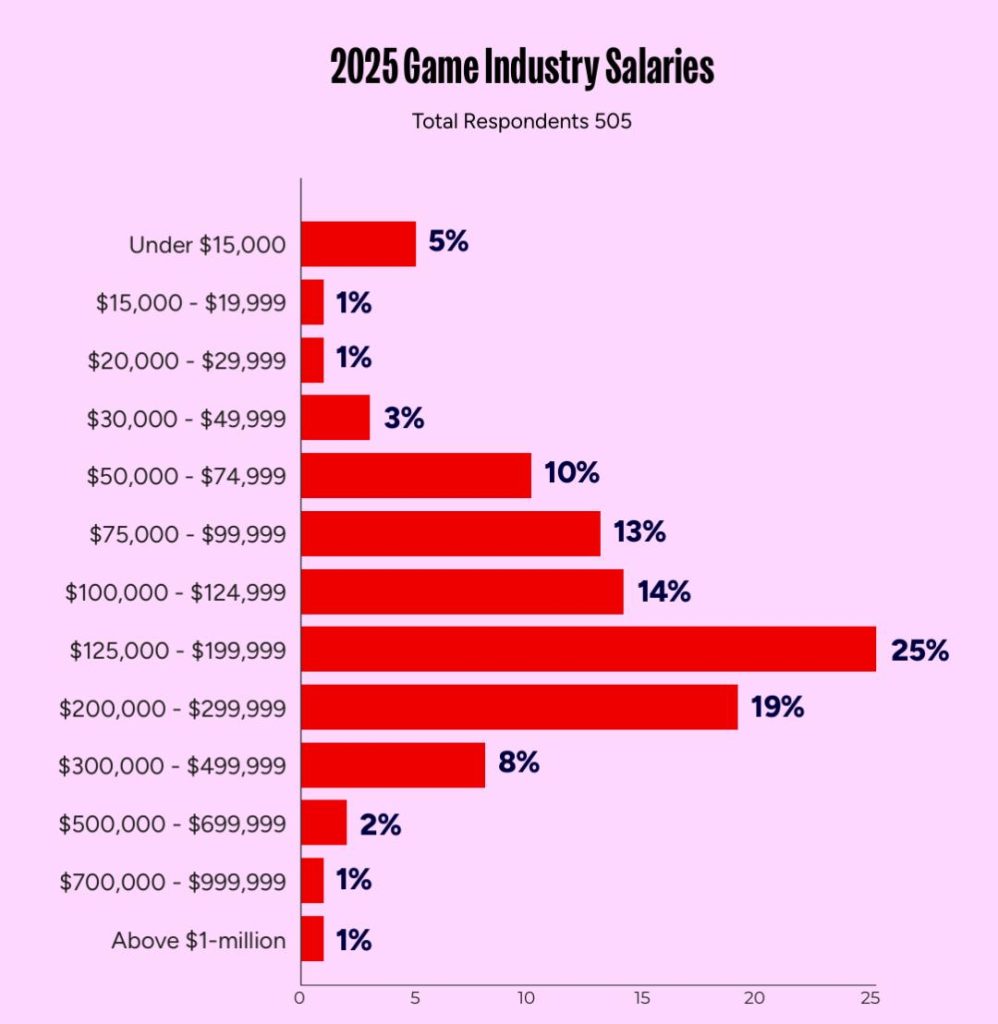

- •56% of respondents expressed dissatisfaction with overall benefits, citing significant pay disparities within the industry. For instance, 5% of workers earn as little as around $15,000 per year.

- •More troubling is the persistent shadow of layoffs since the post-pandemic era: one in four professionals has experienced job cuts in the past two years, and 80% believe the stability of jobs in the gaming industry is lower than in other professions.

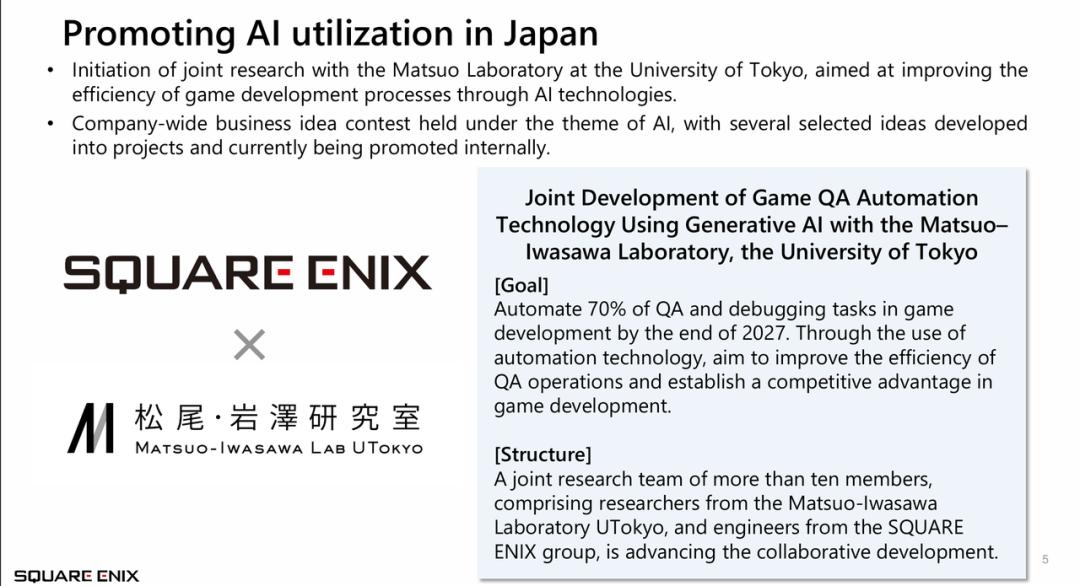

This unease may have taken root during the pandemic. While the industry enjoyed a temporary boom, it also inflated an expansion bubble. When that bubble burst, the once-spectacular fireworks turned into shards that pierced every corner of the industry.Since 2022, the industry has seen slowing growth, compounded by soaring costs and shifting consumer habits. This has triggered a global wave of layoffs.(Unofficial statistics on global layoff trends from 2021 to 2024)Now, as we approach 2026, the aftershocks of the pandemic haven’t fully subsided — and AI is advancing at an even more rapid pace. Far from being a distant concept, AI is now intertwined with layoffs and job restructuring, further straining the stability of the game industry.As a global trend, the aftershocks of the post-pandemic era and the AI wave affect all game professionals equally. So, for those working in games, has stability become a “luxury” rarer than high pay?Let’s take a closer look at the reality faced by American game workers, using insights from the GDC report.

Are U.S. Game Workers Really “Making It”?

At first glance, the numbers suggest they are. As mentioned, the average annual salary is 142,000∗∗,andthe∗∗medianis129,000 — putting most U.S. game professionals in the high-income bracket by global standards.But if you judge the industry solely by these figures, you might misunderstand the true picture. This is not an industry where “any job can easily earn you a seven-figure salary.” Instead, it’s a “bell curve” model where high salaries are concentrated among senior and core roles, and income inequality is just as stark.For example:

- •The most common salary range is 120,000–200,000, accounting for 25% of respondents.

- •However, the top earners (the “high-salary” group) make up 47% of the total, pulling the average upward and widening the gap.

(Salary distribution chart of U.S. game professionals)When broken down by experience level, job role, and studio type, the disparities become even more pronounced.

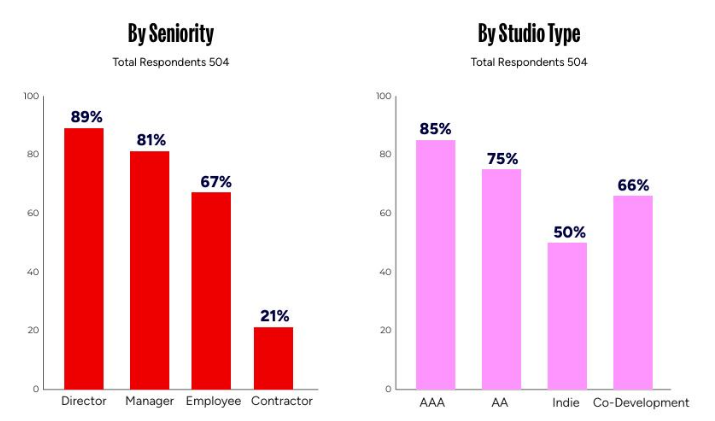

- •Professionals at the Manager level or above almost universally earn at least $100,000 per year (around 81% of Managers earn above this threshold).

- •Around two-thirds of regular employees (Employees) also earn over $100K.

- •In contrast, Contractors (freelancers and outsourced workers) are at a clear disadvantage — only 21% of them earn more than $100,000.

Similarly:

- •At AAA studios, 85% of workers earn over $100,000.

- •Even at independent game studios, half of the employees reach or exceed that level.

This suggests that in the U.S. game industry, individual credentials and job level have a greater impact on salary than the type of studio (AAA, indie, or mid-sized).The report also identified four key factors positively correlated with higher salaries:

- 1.Working at AAA or large studios generally leads to higher pay.

- 2.Internal referrals or being poached often result in better compensation packages.

- 3.Higher job seniority correlates directly with higher salaries.

- 4.Holding a Master’s or PhD degree (especially in technical roles) leads to better pay — although degrees beyond that show diminishing returns.

What these findings reveal is that the high salaries in the U.S. game industry aren’t due to some ongoing “golden age” — that era largely ended with the post-pandemic layoffs. Instead, today’s high compensation is supported by:

- •A highly mature system of specialized roles

- •Decades of accumulated technical expertise in AAA development

- •And the “talent value” built around these capabilities

Unlike their counterparts in China, where developers often wear multiple hats, the U.S. game industry — after decades of evolution — has deeply embedded a culture of specialized division of labor. In the mainstream console game ecosystem, a typical AAA project involves hundreds of cross-disciplinary collaborators: art, engine programming, gameplay design, narrative — each sub-role can be further divided into niche positions, all requiring years of experience.This also explains why, even amid global layoffs, core roles in the U.S. game industry remain highly paid and even more competitive — because in times of contraction, studios are even more reluctant to let go of those with critical expertise.

But Are They Satisfied? Not Really.

Yet, under these high salaries and benefits, most U.S. game professionals still aren’t satisfied.The report surveyed salary satisfaction levels:

- •Only 46% of respondents described themselves as either “reasonably paid,” “slightly overpaid,” or “very well paid.”

- •Meanwhile, 53% felt “slightly underpaid” or “significantly underpaid.”

Clearly, a majority of U.S. game workers feel their current compensation is inadequate.Interestingly, when it comes to work-life balance, only 22% expressed dissatisfaction — suggesting that working hours in the U.S. game industry are still relatively flexible, meeting the desire for a better personal life.However, dissatisfaction with base salary was significantly more common (62%) — even among those earning well into six figures, most still feel they could be earning more.Here’s an important nuance: while many complain about not earning enough, their actual spending power tells a different story.Overall, 83% of respondents said their salaries “adequately,” “well,” or “very well” meet their daily living needs, with only 17% saying their pay is “just enough” or “not enough at all.”This indicates that despite the common refrain of “low pay,” most game workers’ incomes are actually sufficient to cover their expenses. There may be a gap between subjective complaints and objective financial reality.In short, when U.S. game workers say they’re unhappy with their salaries, it’s likely not about financial desperation or burnout from overwork — but rather, a kind of professional pride: “The late nights, the code I write, the crunch I endure — it’s all worth this much.”From the perspective of workers everywhere, I hope that in this uncertain era, more underpaid and undervalued game professionals — treated like disposable batteries — can find their voice, just like their U.S. counterparts, and fight for their rights through legal and constructive means.

The Underlying Anxiety: Uncertainty About the Industry’s Future

So, if U.S. game workers are generally well-paid and their salaries are sufficient for a comfortable life, why does this strange tension around money persist?The answer may lie in their deep-seated anxiety about the unpredictable future of the game industry — a manifestation of “preparing for the worst.”As we noted earlier, U.S. game professionals are grappling with far more serious concerns than we might imagine — pandemic aftershocks, AI disruption, and ongoing layoffs have created a level of uncertainty that runs deeper than the surface numbers suggest.